Inside the New Stew Leonard's, Master of Fresh

If you walked into the Stew Leonard’s grocery store in Paramus, N.J., on Sept. 16, a couple of days ahead of its official grand-opening date, you would have been greeted by a live brown cow mooing near the bananas and grapes in the produce department.

Martha, a New Jersey-born heifer named after culinary star Martha Stewart, was brought in from Cloverland Farm, in Frenchtown, N.J., to celebrate the store’s grand opening, a fitting tribute to this small grocery chain’s history and to its value proposition for shoppers today.

At a Glance

Stew Leonard’s

700 Paramus Park

Paramus, NJ 07652

Opening date: Sept. 18, 2019

Hours: Monday-Saturday 8 a.m.-10 p.m.

Sunday 8 a.m.-9 p.m.

Total square footage: 100,000 (includes upstairs offices and party room)

Selling area in square feet: 40,000

Employees: 400

Number of checkouts: 25

Designer: Richard Lung, Stew Leonard's director of art and advertising

After all, Stew Leonard’s, a northeastern chain of grocery stores based in Norwalk, Conn., began as a dairy.

In the early 1920s, Charles Leonard founded a milk delivery company called Clover Farms Dairy in Norwalk. In 1969, the Leonard family moved the dairy plant to another location in Norwalk and opened a small storefront. Eventually, the company expanded that store by adding meat, seafood and other departments, including eclectic features such as a petting zoo and animatronic puppets (the company’s founder was a big fan of Walt Disney).

Over the decades, the still-family-owned retailer’s reputation for top-quality fresh food, unique private-brand products and a “Disney-esque” shopping experience have fueled so much devotion from shoppers that the company has grown into a seven-store chain with annual sales of $500 million.

“What we’re trying to do is really create a fun experience in the store,” explains President and CEO Stew Leonard Jr. “That’s the big challenge that all retailers have today. There’s going to be grocery items that shoppers are going to buy over the Internet, like canned food or laundry detergent. Why go to a store for that? So what we try to do is make a big splash in fresh food and create a theatrical environment to make grocery shopping in the store fun.”

Leonard isn’t kidding when he talks about fresh food or theatrics: 80% of the assortment in each Stew Leonard’s store is fresh food. When a shopper walks into the Paramus store, for example, the aromas from the mostly scratch bakery and other fresh departments are mesmerizing. Want a fresh-dipped ice cream cone, a craft cappuccino, a hot cup of clam chowder or a chocolate-chip scone right out of the oven? Stew Leonard’s has all of it, made fresh.

The grocer fries its own apple cider doughnuts, boils its own bagels, pulls its own mozzarella, bakes its own pretzels, griddles its own tortillas and butchers its own meats, all of which can be cut to order. Prepared foods run the gamut from cauliflower-crust pizza (“a big seller”), to every kind of chicken wing preparation known to man, to the most fragrant Thai and Indian dishes — all made on-site. Stew Leonard’s even makes its own ice cream and butter and processes its own milk.

At the 80,000-square-foot Paramus store, parents push shopping carts occupied by children visibly in awe of the singing avocado girl puppets near the fruit and vegetable butcher, or the animatronic milk cartons performing their catchy numbers near the dairy case.

By creating this theatrical fresh food value proposition, Stew Leonard’s believes that it’s ahead of consumer trends, giving it more than a fighting chance to win the battle against discounters, ecommerce giants and even the big grocery chains, many of which are still behind the eight ball in responding to the way consumers shop today.

Modern grocery shoppers, especially Millennials and Gen Zers, want stores that offer more fresh food and “amazing food experiences.” Stew Leonard’s believes it offers all of that — and more.

Farmers’ Market Fun

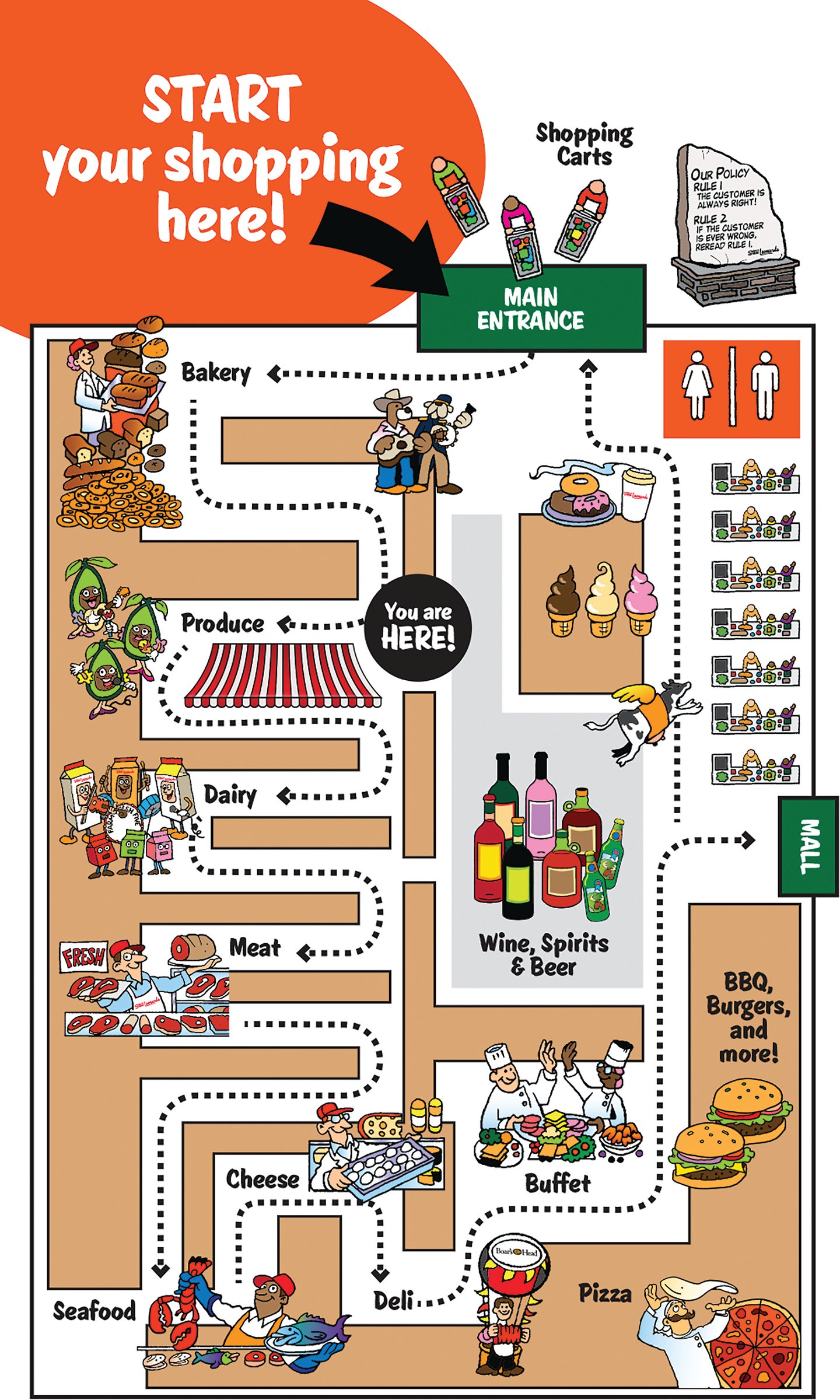

Each Stew Leonard’s store, including the new one in Paramus (a wealthy suburb of New York City), has a rustic, farmer’s market-style façade. Inside, a single one-way aisle winds through the store in a zigzag, similar to the experience of walking through an attraction at Disney World.

According to company leaders, the design gives the consumer an immersive experience in fresh, aromatic food; wholesome entertainment; and a “customer comes first” congeniality. In fact, the first thing a shopper sees upon entering each Stew Leonard’s store is a sign: “Rule 1: The Customer Is Always Right! Rule 2: If The Customer Is Ever Wrong, Reread Rule 1.”

“Stew isn’t just my grandfather’s name — S-T-E-W is an acronym for our core values,” observes Jake Tavello, Stew Leonard Jr.’s nephew, VP of the store in Paramus and a recent Progressive Grocer GenNext Award Honoree. “S stands for service, as in providing great customer service. T stands for teamwork, having a great place to work. E stands for excellence, as in offering high quality. And W is for wow, wowing customers with our fresh food, animatronics, store events, promotions or giveaways.”

Despite his connections, Tavello had to meet the company’s strict requirements for all Leonard family members wanting to join the business. They must work three years for another company, get a master’s degree and interview with an executive panel for the job. He paid his dues by putting in three years at Rochester, N.Y.-based Wegmans Food Markets.

“Wegmans has done a fantastic job,” Tavello says. “They’re a generation ahead of us, so they’re where we’d love to be. They have a great model, but it was interesting to see how ideas evolved there. There’d be a lot of different steps in order to implement an idea and get it into action. And I think where we fit into the marketplace is, we can be agile. So if we see a trend, we’re just going to try and get it started right away.”

Since its founding in 1969, the company has grown slowly, not opening its second store until 1992. A third store followed, in Yonkers, N.Y., in 1999, and a fourth store opened in 2007. Since then, the retailer has accelerated its expansion aspirations and opened new stores in 2016, 2017 and, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the company, its seventh and first New Jersey location this year. Many Stew Leonard’s stores span more than 100,000 square feet, but beginning in 2017, the company decided to “downsize” to a format of about 80,000 square feet. The company doesn’t have a central warehouse, so all products come directly to each store.

“Our Paramus store is already doing really well,” Leonard says. “We don’t have aggressive expansion plans, but if something exciting comes our way, we’ll probably go with it. I can definitely see that going smaller is better. We have even talked about doing something like a Stew Junior-type store, an even smaller format.”

So how does the company plan to offer its famous fresh food theatrics in a smaller format? “I think you can still keep the same energy and experience in the store, but just go smaller,” Leonard replies.

Despite its recent ramped-up growth, the company says that for now, it’s hitting the pause button and focusing on operations. Each store has a VP to the c-level executives, with two store directors under the VP. Many managers and other senior-level folks have been moved around as the company has expanded, leading to a sort of restructuring phase for the retailer.

“We’ve loved expanding, but I think in the short term, we’re gonna need to rebuild a little bit,” Tavello notes. “One of the things that makes our family proud is that we’ve hired 80% of our management team from within.”

Tavello adds that the grocer’s operational priorities for the coming year include increasing efficiencies when it comes to staff hours and production, despite an ever-tightening labor market.

“Focusing on fresh food takes a lot of labor and time,” he says. “We’re going to have to become more efficient with that and find better ways to do that. We had to interview about 25% more people to open the Paramus store than we did with our previous stores. Plus, with $15 an hour in our operating states, there’s this constant pressure on labor. Managing our business model, making a lot of fresh food, as wages have kept growing, is definitely going to be a challenge.”

The company has acquired new technology “that’s going to really help us try to match the sales in the store with the labor hours,” Leonard observes. “What we want to do is make sure we have the right number of people at the right times to help the customer.”

A Brand of Their Own

Another priority for the company is constantly improving its assortment. The average grocery store stocks approximately 40,000 SKUs; Stew Leonard’s offers around 2,000. Center store products are few, because the stores have such a laser focus on fresh. Overall, its private brand penetration is 60%.

“Frankly, I’d like to be all private label,” Leonard confides, adding that the combination of fresh food that’s also private branded is proving irresistible to modern shoppers who’ve come to depend on private brands for quality and value often no longer found in national brands.

“People are reading labels more than they ever have in the past,” Leonard continues. “We have a private-brand marinara sauce that we just introduced that’s just rocketed. No sugar added or anything like that. So I think for our private label, we have to be clean. And the second thing I think people really resonate with is local. So we’re getting some chips made from a local family in Connecticut. Those are the things that today’s customers want.”

According to the grocer, shoppers at the Paramus store are asking for more kosher, gluten-free and organic meats. Interestingly, despite the retailer’s fresh food focus, consumer interest in frozen foods has increased as quality in that category has edged up (the Paramus store has 25% more freezer doors than Stew Leonard's previous stores).

Delivering Fresh

Beyond Stew Leonard’s animatronic puppet shows, fresh food and private brands, Tavello takes pride in the fact that the company has finally embraced big data and delivery.

“Going forward, you can’t be just one channel,” he asserts. “Even though we’re focused on fresh and customer experience, sometimes people don’t have time for the store. Our delivery offering through Instacart has been a huge hit.” He says that the company is “doing 1,000 orders a week” through Instacart.

“What we’ve noticed is, when shoppers trust your quality and your brand, they’re going to trust having your products delivered,” Tavello notes, “and actually, what we found is they are spending twice as much online as they would if they were coming to the store.”

The company plans to work on harnessing all of the data from deliveries, and its new app, launched this year, to better understand its customers.

“Our growth areas for the future include those grab-and-go convenience items,” Tavello says. “We have a team that just works on developing those. Obviously, delivery is a big growth driver for us. And just staying focused on fresh, even though that’s nothing new for us. But the categories that are growing are really the fresh items.”